- Home

- Dalia Sofer

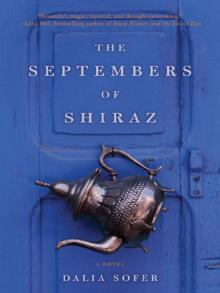

The Septembers of Shiraz

The Septembers of Shiraz Read online

THE SEPTEMBERS OF SHIRAZ

DALIA SOFER

For my parents, Simon and Farah,

my brothers, Joseph and Alfred,

and my sister, Orly

CONTENTS

ONE

When Isaac Amin sees two men with rifles walk into…

TWO

The guard, Hossein, stands by the door of the cell…

THREE

In the dark Farnaz traces the outlines of the furniture—…

FOUR

The chant of the muezzin fills the cloudless sky above…

FIVE

A draft blows through his window. It’s going to be…

SIX

For days her mother’s sapphire ring has been missing.

SEVEN

Inside the house, perched on the curves of the Niavaran…

EIGHT

“Homayoun…Gholampour…Habibi…” A guard yells out the names as…

NINE

Of prisons, she knows little. The Tower of London, the…

TEN

Parviz’s exit out of the subway coincides with the end…

ELEVEN

Leila’s family seems to live on the floor—the floor…

TWELVE

Once a week the prisoners are allowed to spend an…

THIRTEEN

Here they play solitaire and old songs. A 1950s recording…

FOURTEEN

A good structure, like a good man or woman, must…

FIFTEEN

Absence, Shirin thinks, is death’s cousin. One day something is…

SIXTEEN

Isaac watches the dark clouds through the shoebox window, smells…

SEVENTEEN

When they arrive, on an overcast afternoon in December, Farnaz…

EIGHTEEN

New York loves expanse. It grows upward and spreads its…

NINETEEN

Musical chairs in Leila’s house means musical cushions. Shirin and…

TWENTY

Isaac stares at his hands—the skeletal knuckles, the dark…

TWENTY-ONE

On the other side of the office gates there is…

TWENTY-TWO

“What’s your favorite flower?” Rachel says.

TWENTY-THREE

Ramin’s mother and old man Muhammad’s eldest daughter were killed…

TWENTY-FOUR

Five couplets, at the minimum, but no more than twelve…

TWENTY-FIVE

The kitchen simmers in the heat of radiators and the…

TWENTY-SIX

Standing by the statue of Shakespeare under the trees and…

TWENTY-SEVEN

Isaac stretches his legs, tapping them with his fingers to…

TWENTY-EIGHT

To kill time before her meeting with Isaac’s brother, Farnaz…

TWENTY-NINE

Isaac stands on one leg. He has lifted the other…

THIRTY

At the breakfast table Shirin rests her sleepy head on…

THIRTY-ONE

Everytime she looks at her reflection in the oval mirror,…

THIRTY-TWO

His sister answers the phone. “Parviz!” she says.

THIRTY-THREE

A few early risers are at the teahouse, sipping and…

THIRTY-FOUR

He sees his world in black and white: Filthy snow,…

THIRTY-FIVE

Walking in the rain, Shirin watches people’s expressions hardening, the…

THIRTY-SIX

What jars him out of sleep is not the sound…

THIRTY-SEVEN

He smells of sweat, and blood, and of something else,…

THIRTY-EIGHT

Habibeh chops off a fish’s head and slides it into…

THIRTY-NINE

Rachel bursts through the door, flushed and out of breath.…

FORTY

His desk is the only object in the office left…

FORTY-ONE

Isaac brings the scissors to his chin and clips off…

FORTY-TWO

Reclining against the wall and hugging one knee, the boyish…

FORTY-THREE

In the car, on the way to the Caspian, where…

FORTY-FOUR

A festive spirit fills the Mendelson household for many days…

FORTY-FIVE

Any moment now, Isaac knows, his father will die. Afterward,…

FORTY-SIX

A letter arrives, from a certain “Jacques Amande,” postmarked Paris:…

FORTY-SEVEN

Isaac sips his tea at the kitchen table. Sunrise is…

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

ONE

When Isaac Amin sees two men with rifles walk into his office at half past noon on a warm autumn day in Tehran, his first thought is that he won’t be able to join his wife and daughter for lunch, as promised.

“Brother Amin?” the shorter of the men says.

Isaac nods. A few months ago they took his friend Kourosh Nassiri, and just weeks later news got around that Ali the baker had disappeared.

“We’re here by orders of the Revolutionary Guards.” The smaller man points his rifle directly at Isaac and walks toward him, his steps too long for his legs. “You are under arrest, Brother.”

Isaac shuts the inventory notebook before him. He looks down at his desk, at the indifferent items witnessing this event—the scattered files, a metal paperweight, a box of Dunhill cigarettes, a crystal ashtray, and a cup of tea, freshly brewed, two mint leaves floating inside. His calendar is spread open and he stares at it, at today’s date, September 20, 1981, at the notes scribbled on the page—call Mr. Nakamura regarding pearls, lunch at home, receive shipment of black opals from Australia around 3:00 PM, pick up shoes from cobbler—appointments he won’t be keeping. On the opposite page is a glossy photo of the Hafez mausoleum in Shiraz. Under it are the words, “City of Poets and Roses.”

“May I see your papers?” Isaac asks.

“Papers?” the man chuckles. “Brother, don’t concern yourself with papers.”

The other man, silent until now, takes a few steps. “You are Brother Amin, correct?” he asks.

“Yes.”

“Then please follow us.”

He examines the rifles again, the short man’s stubby finger already on the trigger, so he gets up, and with the two men makes his way down his five-story office building, which seems strangely deserted. In the morning he had noticed that only nine of his sixteen employees had come to work, but he had thought nothing of it; people had been unpredictable lately. Now he wonders where they are. Had they known?

As they reach the pavement he senses the sun spreading down his neck and back. He feels calm, almost numb, and he reminds himself he should remain so. A black motorcycle is parked by the curb, next to his own polished, emerald-green Jaguar. The small man smirks at the sleek automobile, then mounts his motorcycle, releases the brake, and ignites the engine. Isaac mounts next, with the second soldier behind him. “Hold on tight,” the soldier says. Isaac’s arms girdle the small man and the third man rests his hands on Isaac’s waist. Sandwiched between the two he feels the bony back of one against his stomach and the belly of the other pushing into his back. The bitter smell of unwashed hair makes him gag. Turning his head to take a breath, he glimpses one of his employees, Morteza, frozen on the sidewalk like a bystander at a funeral procession.

The motorcycle swerves through the narrow spaces between jammed cars. He watches the city glide by, its transformation now so obvious to him: movie posters and shampoo advertisem

ents have been replaced by sweeping murals of clerics; streets once named after kings now claim the revolution as their patron; and once-dapper men and women have become bearded shadows and black veils. The smell of kebab and charcoaled corn, rising from the street vendor’s grill, fills the lunch hour. He had often treated himself to a hot skewer of lamb kebab here, sometimes bringing back two dozen for his employees, who would congregate in the kitchen, slide the tender meat off the skewers with slices of bread, and chew loudly. Isaac joined them from time to time, and while he could not allow himself to eat with equal abandon, he would be pleased for having initiated the gathering.

The vendor, fanning his grilled meat, looks at Isaac on the motorcycle, stupefied. Isaac looks back, but his captors pick up speed and he feels dizzy all of a sudden, ready to topple over. He locks his fingers around the driver’s girth.

They stop at an unassuming gray building, dismount the bike, and enter. Greetings are exchanged among the revolutionaries and Isaac is led to a room smelling of sweat and feet. The room is small, maybe one-fifth the size of his living room, with mustard-yellow walls. He is seated on a bench, already filled with about a dozen men. He is squeezed between a middle-aged man and a young boy of sixteen or seventeen.

“I don’t know how they keep adding more people on this bench,” the man next to him mumbles, as though to himself but loudly enough for Isaac to hear. Isaac notices the man is wearing pajama pants with socks and shoes.

“How long have you been here?” he asks, deciding that the man’s hostility has little to do with him.

“I’m not sure,” says the man. “They came to my house in the middle of the night. My wife was hysterical. She insisted on making me a cheese sandwich before I left. I don’t know what got into her. She cut the cheese, her hands shaking. She even put in some parsley and radishes. As she was about to hand me the sandwich one of the soldiers grabbed it from her, ate it in three or four bites, and said, ‘Thanks, Sister. How did you know I was starving?’” Hearing this story makes Isaac feel fortunate; his family at least had been spared a similar scene. “This bench is killing my back,” the man continues. “And they won’t even let me use the bathroom.”

Isaac rests his head against the wall. How odd that he should get arrested today of all days, when he was going to make up his long absences to his wife and daughter by joining them for lunch. For months he had been leaving the house at dawn, when the snow-covered Elburz Mountains slowly unveiled themselves in the red-orange light, and the city shook itself out of sleep, lights in bedrooms and kitchens coming on one after the other, languidly at first, then gaining momentum. And he had been returning from the office long after the supper dishes had been washed and stored away and Shirin had gone to bed. At night, walking up the stairs of his two-story villa, he could already hear the television buzzing, and in the living room he would find Farnaz, in her silk nightgown, cognac in hand, soaking up the chaos of the evening news. The cognac, she said—its stinging vapors, its roundness and warmth—made the news more palatable, and Isaac did not object to this new habit of hers, which, he suspected, made up for his absences. In the living room he would stand next to her, his briefcase an extension of his hand, neither sitting beside her nor ignoring her; standing was all he could manage. They would say little to each other, a few words about the day or Shirin or some explosion somewhere, and he would retire to the bedroom, exhausted, trying to sleep but unable, the television’s drone seeping into the darkness. Lying awake in bed he would often think that if she would only shut off the news and come to him, he would remember how to talk to her. But the television, with its images of rioting crowds and burning movie theaters—with its wretched footage of his country coming undone, street by street—had taken his place long before he had learned to find refuge in his work, long even before the cognac had become necessary.

THREE GUARDS ARRIVE and hand out rice-filled metal bowls. He examines the food; what if it’s poisoned? The thought must have occurred to the others, as there isn’t a sound in the room. “Eat, you fools!” a guard bellows. “You don’t know when your next meal will be coming.” Utensils clatter. The rice is dry and tasteless, and undercooked lentils, thrown in like an afterthought, crack between Isaac’s teeth. But he is hungry and decides to finish it all.

“Agha—sir!” the man in pajamas cries to one of the guards. “Please. I must go to the bathroom.” The guard watches him for a while, then leaves, uninterested. The man coils into himself. He doesn’t eat.

Isaac chews and replays the events of that afternoon—how the moment he had seen their shadows in the dim corridor outside his office he had capped his fountain pen and put it down, surrendering before they had even opened their mouths; how absurd everything since that moment feels to him now. For the first time since his arrest he realizes what just happened to him: that his life, if anything is to remain of it, will be different from this day on. That he may never touch his wife again, that he may never see his daughter grow up, that the day he stood at the airport, waving good-bye to his son who was leaving for New York, may have been the last time he sees him. As he considers these things, a hand slides into his. Isaac flinches, turns his head.

“Hello. I’m Ramin,” the boy next to him says.

Isaac looks into the boy’s wide, dark eyes, and recognizes in them his own terror, which he has been trying to suppress all afternoon. The boy’s hand is cold, the fingers like bits of ice.

“How old are you?”

“Sixteen.”

Two years younger than his son, Parviz. “Your parents know you’re here?”

“My father is dead. And my mother is already in jail. It’s been two months.”

“They won’t keep you long,” Isaac says. “You’re just a boy.”

Ramin nods, takes a deep breath. The reassurance—which Isaac offered out of fatherly instinct rather than actual belief—seems to have calmed him.

“Why do you think they’re keeping us here?” the boy continues. “Are they trying to decide which prison to send us to?”

“Keep it down!” A guard’s voice pierces the hush that has settled about the room, like dust. “Don’t aggravate your case!”

They obey, sit in silence. Isaac imagines Ramin’s story. His family could be related to the shah. Or maybe he is one of those hot-blooded communists, protesting the new Islamic regime as they had the old monarchy. Or maybe it’s simpler than all that. He could be a Jew, like Isaac, or worse, of the Baha’i faith, believing that all of humanity is one race, and that there is a single religion—that of God.

From his left he hears water trickling onto the floor. “Forgive me,” the man who had been sitting next to him says. He is standing in a corner, his back to the others, a yellow puddle forming by his feet and streaming to the middle of the room. A few men shift uncomfortably in their seats. “I can’t hold it any longer,” he says. “I’m sorry.”

Isaac looks at the man—the deep burgundy of his pajama pants, the sheen of his leather shoes—seamless, solid, perfect—hand-stitched no doubt in a dusty atelier in the outskirts of London or Milan. These accessories, hints of the life the man has left behind, make Isaac pity him more. They are all the same here, he realizes, the remnants of the shah’s entourage and the powerful businessmen and the communist rebels and the bakers and bazaar vendors and watchmakers. In this room, stripped of their ornaments and belongings, they are nothing more than bodies, each as likely as the next to face a firing squad or to go home, unscathed, with a gripping tale to tell friends and family.

He shuts his eyes, tries not to think about his wife’s salty laughter, his son’s easy smile, the curlicues of his daughter’s hair. When he opens his eyes he sees a man towering above him, his body framed by a light from the lone bulb dangling from the ceiling. “Get up,” the man says.

Isaac rises to his feet but his knees, locked into place like rusted doorknobs, make him fall back on the bench. The man remains stern, manila folder under his arm; he offers no help. Isaac tries

again, stands up this time. The man removes Isaac’s watch and unbuckles his belt; he slides these into the pocket of his green jacket. Then he unties a handkerchief from his wrist and blindfolds Isaac, weaving a double knot in the back of his head and pulling hard on the cloth. Isaac feels his lashes fastened to his face, his castrated eyes submerged in blackness. Already he misses his once effortless capacity to blink—this smallest of movements. He is led out of the building and onto the street. The afternoon traffic drowns the sound of his footsteps. Wooden clogs approach him, reminding him of his daughter’s footsteps, and as the sound intensifies it brings along a child’s voice, “Mama—look! That man. What has he done?” Deprived of his vision, he has forgotten that others can still see. He feels embarrassed, hopes people are not chattering about him by their doorways and windows. The tip of a rifle nudges the small of his back. “Faster!” the man commands. “You think we’re going for a stroll?” Isaac picks up the pace.

He is seated in the back of a van, between two men, one of whom smells like cigarette smoke and rose water. As he listens to the engine’s shifting roar and the guards’ logistical banter—whom should they pick up next, should they stop for gas?—he tries to match voices with faces he had seen earlier, but he realizes that he recalls nothing of his captors. Their clothes had been shabby, that much he can say. And the last one, the one who had blindfolded him, was spade-bearded. But faces, they had none.

Man of My Time

Man of My Time The Septembers of Shiraz

The Septembers of Shiraz